by Caroline Walker

I have a nice personal memory of Professor Tim Lang. In 2001 I had just retired as head of the Small School in Hartland, North Devon, a very small independent secondary school where cooking the lunch together was a foundational practice. I heard about the Caroline Walker (no relation) Awards which recognise good practice in food and nutrition and decided to put forward our school’s approach to growing, cooking and eating food. To my great delight we won the award for “Contribution to public health through good nutrition”. Tim Lang happened to be sitting behind me and and as our name was announced as a winner, kindly put a hand on my shoulder and said, “Well done!”

Professor Lang is one of the leading experts, as well as a veteran (and pretty exasperated) campaigner on food issues, and I have drawn on his recent book Feeding Britain: Our Food Problems and How to Fix Them for this short article. I have also taken inspiration from Simon Fairlie’s 2008 paper Can Britain feed itself? published in The Land magazine, from the Growing Through Climate Change paper commissioned by Alan Heeks and from a recent book by Somerset farmer Chris Smaje A Small Farm Future.

Public policies drawn up by those in power determine what food is grown and imported, what food is available in the shops, where food retail outlets are situated, and who has access to land, tools, seeds and skills. They also influence access to shops, the time and ability people have to go shopping, the cost and affordability of food, and how the food is stored in homes. Health and education policies promote (or not) skills in cooking and knowledge of nutrition, and advertising and the media, supposedly subject to legislation, influence what food we want, like, buy and consume.

It’s a complex and little-understood issue: when you ask (as I have) a group of teenagers, “Where does your food come from?” generally they will say “From the fridge.” Studies have revealed shocking rises in food poverty and in the number of young children living in households which are ‘severely food-insecure’. This is one area where unfortunately we top the chart of countries in Europe. The impact on the health of these children will be long-lasting, and the price paid by society as a whole. Malnutrition (too little food, or too much unhealthy food) is making us ill, with diet-related diseases on the increase.

So individually we are not food-secure. The national picture is no better. We no longer have any colonies to give us preferential trade deals as in the past, nor do we have the defence capability to protect our supply chains. The UK is not self-sufficient in food:

In sector terms, the UK self sufficiency is 62% in cereals, 75% in red meat, 77% in dairy and only 23% in fruit and vegetables.

Based on farmgate value of unprocessed food, just under 50% of food consumed in the UK was provided by the UK itself. Other EU countries provided 30%, and 4% each came from Africa, Asia, North America and South America.

(source: Feeding Britain)

In sector terms, the UK self sufficiency is 62% in cereals, 75% in red meat, 77% in dairy and only 23% in fruit and vegetables.

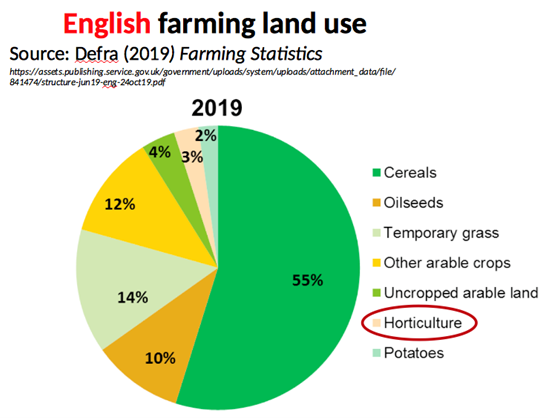

We are especially not secure as far as fruit and vegetables are concerned. There is a trade gap in this sector of £9.85bn (figure from 2018). Land used for horticulture is a mere 168,000 ha out of the UK’s 18.8 mha. Land that used to be used for fruit and vegetable growing has been lost, greenhouses left derelict, orchards grubbed up. Possibly, with higher prices for food imports after Brexit, this trend may reverse? The figures for meat and dairy seem a little reassuring; but land that could be used to feed us produces grain to feed cattle that then only partially feed us. As Lang says, ‘we are a species which has outgrown its niche, and cattle are our competitors’.

The trade gap is enormous and the effects of Brexit are going to be catastrophic, according to many commentators. We already hear of long queues of lorries stuck at ports. Some will surely be carrying perishable foodstuffs. There is a real danger of food shortages and of the collapse of our ‘just-in-time’ distribution system. Then there is the additional threat that we may have great difficulty in attracting migrant labour to our farms and even greater difficulty attracting home-grown labour. Work in fields and abattoirs and meat processing plants is dangerous, dirty and low paid – which is why we have to import people from poorer countries to do it. Lang’s book lays out in great detail, with a wealth of supporting statistics and documentation, these and many more challenges to our food security.

We are fortunate here in the south west to have a mild climate and many local food producers. There is potential to increase the amount, variety and quality of food grown locally (and sustainably) but only if training for land-based skills is improved; Bicton College, for example, has countryside management courses but I couldn’t find any vegetable growing course. And Seal Hayne Agricultural College closed in 2005. The work of Schumacher College in promoting sustainable agro-forestry and horticulture should be commended but the number of places is small.

What is Tim Lang’s recipe for improving the situation?

We need more people from the UK to commit to working in the food sector; set goals to increase sustainable production of food, especially vegetables and fruit; grow more for home consumption, not export; and introduce more diversity into our food crops, especially in the light of a changing climate. The grain we grow should feed us, not animals: in Lang’s terms, we should ‘walk livestock back into its ecological niche’ which might mean moving to high quality grass-fed meat on land unsuitable for anything else, and feeding pigs on crop residues. Farmers need to reskill to fill the gaps in fruit and vegetable growing, and most importantly, land should be identified and released for young growers.

Perhaps we need a movement like Vinoba Bhave’s in India in the mid twentieth century: he walked the length and breadth of India persuading large landowners to give him a portion of their land which was then distributed to the landless. I wonder how many landowners would be so community-minded? (Many of them are probably shell companies based in the Cayman Islands anyway.)

I recommend Lang’s book to anyone who wants to explore further, and will end with a tentatively hopeful quote from Chris Smaje, a powerful advocate of small farms:

“It’s true that Britain has long been a net importer of food, yet throughout this time there have been people arguing that it can and should largely feed itself. They weren’t necessarily wrong, they just lost the political argument. Maybe their successors will be luckier.”